Prison Envy

I grew up in farm country South Dakota, where I heard a lot of Johnny Cash. I loved his voice. It sounded like a rusted muffler, but it moved me. So I’ve listened with interest and pleasure to Johnny’s daughter, singer, song-writer Rosanne Cash who’s earned her own place in American music. When someone offered me tickets to hear Rosanne Cash at a benefit concert on Sunday, I jumped.

I grew up in farm country South Dakota, where I heard a lot of Johnny Cash. I loved his voice. It sounded like a rusted muffler, but it moved me. So I’ve listened with interest and pleasure to Johnny’s daughter, singer, song-writer Rosanne Cash who’s earned her own place in American music. When someone offered me tickets to hear Rosanne Cash at a benefit concert on Sunday, I jumped.

Sunday’s event was in support of “Family Re-entry,” an organization that works with ex-convicts and their families. Everybody knows that term recidivism, the tendency to relapse into a former behavior and end up back behind bars. Prisons are what Sunny Schwartz calls “monster factories.” When the cell door opens and the ex-con walks out, it’s almost impossible to live a different life.

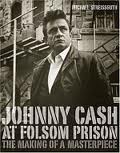

It seemed right that Rosanne Cash should take the stage Sunday. Her father had served hard time, had sung about it in “Folsom Prison Blues,” had stunned the music world when—against the advice of his manager, agent and record studio—he played Folsom Prison in 1968. Johnny Cash knew prisons and prisoners. He knew about bondage and freedom.

But most of us 500 people sitting under a white tent pitched on the vast lawns of a Greenwich estate did not. We sat transfixed as ex-cons took the stage to tell their stories. With the exception of Dena, a slight woman whose alcohol-fueled blow-out had landed her twice in the big house, they were all black men, most of them the size of a defensive tackle. Chris, who had been in and out of federal prison, thanked the mentor who helped him to jump from the runaway train to destruction. “I want to thank my mother,” Chris said, pointing to a woman sitting at a table. “She’s been my rock.” (An older woman sitting next to me tugged at my elbow and whispered, “I wonder what he did. He’s such a beautiful man.” I whispered back that you don’t go to federal prison for shoplifting.) Then George stood and said, flatly, that he would not be alive, standing here today if not for the people who met him at the prison gate and walked with him into a new life. “I want to thank the people who saved my life,” George said, “and I want to ask them to stand.” He called their names, and they stood. Utter love flowed between them at thirty yards.

I could not imagine standing in front of 500 people and pointing out the people who had “saved my life.” Standing there and admitting that I was as good as dead, that I had failed and made a mess of things, that I needed help, bad. That would be humiliating. Then why were all of us (mostly) white (mostly) privileged people sitting there admiring these people, marveling at their power, their energy for living?

Somehow we have to learn how to fall, or find the fallen one deep down inside—hidden inside the perfectly turned out façade. That’s when life gets real, gets powerful, exciting, painful, gets exhilarating and frightening both, gets clear and true and beautiful. For us who will never commit a crime obvious enough to land us in prison, what can we do?

Here’s to learing how to fall!

If you are a Johnny Cash fan, and you have not yet seen Million Dollar Quartet, see it! the guy protraying Cash sounds more like Cash than Cash did!

David, I love your blog. It sounds like you–and makes me feel that we’re sitting in front of a coffee shop over a cup. Also, Ralph and I share your enthusiasm for Roseanne Cash. We’ve heard her twice–once at a fancy- pants concert in Washington and again with the kids under the stars on Cape Cod. But there’s nothing like her dad’s rusted out voice. Your voice is strong, and it inspires. Thank you for doing this.