Holy Envy

As a priest, I’ve officiated at hundreds of weddings, but Friday I attended my first Nigerian wedding.

If you remember the scene in My Big Fat Greek Wedding, when the conservative, understated parents of the WASPy groom first meet the bride’s big, boisterous Greek family, you know how I felt walking into the banquet hall.

The music is pulsing. Nigerian women all bedecked in heavily beaded green gowns with Gele head ties swirling above, men in purple dashikis with Fila caps on their heads. A Nigerian minister offers an opening prayer, but this rollicking ritual is conducted by the “aunties,” the elder women. Whole extended families make an entrance and are introduced, one by one. The Groom doesn’t just walk in, he dances in, surrounded by his men. The Bride and her ladies, hidden behind green feathered fans, swirl and glide into the hall. I am mesmerized.

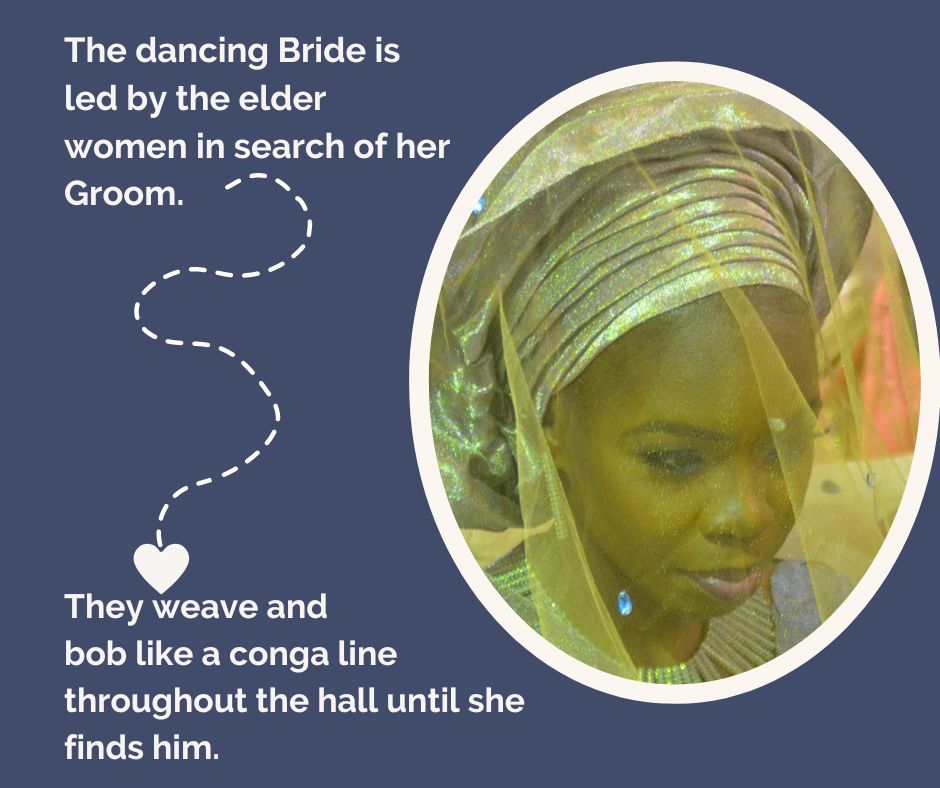

The dancing Bride is led by the elder women in search of her Groom. They weave and bob like a conga line throughout the hall until she finds him. Together they kneel before their parents, who lay on hands and offer prayers of deep blessing, then kneel before elders, brothers and sisters, some so close they scoot on knees from one to the next.

Tomorrow is the Episcopal service where I will be presiding, and for a moment I want a ceremony like this. We will all walk in—no dancing from place to place—and we will say many words, beautiful words. We will stand, stately. No one will walk on knees for a mother’s blessing. The congregation will sit in straight rows, and no one will move. Our liturgy has a beauty of its own, I know, but I’m feeling what Krister Stendahl called “holy envy”—when we experience another faith tradition and wish ours had a similar practice. Doesn’t mean we ditch our faith. It just means we recognize that all traditions are limited, ours included, and that we have much to receive from those who seem so unlike us.

When Saturday arrived, the familiar liturgy was more beautiful than I remembered, the vows more powerful, the string quartet more stirring. Having run its course, holy envy now gave way to quiet gratitude for old treasures long taken for granted.

That Nigerian wedding sounds amazing! What a picture you painted! There is something to be said for pure, unadulterated joy that it seems most Caucasians can find only with the help of alcohol and/or drugs. Weird, right?!

So true, Matt—if we don’t find some way to fall into ecstatic experience, many of us end up trying to get there via some chemical or another.

Hey David, loved this piece, first, because it reminded me of a Nigerian wedding I presided at for a young man from my parish in Illinois. The wedding had all the elements you describe. I’ll go now and find those photos.

But also for “holy envy.” Now I have a name for what I’ve felt for years, decades! Not just at that Nigerian wedding but even more so whenever I worship in a fundamentalist or evangelical church, even a mega-church with the big praise team and the big, loud rock band. Though it’s very different from little Calvary Baptist in little Yankton, “holy envy” is very much there. Holy envy on holy ground.

But then, you’re right, when I return to St. Philip’s, our Anglo-Catholic parish here in Tucson, with its solemn liturgy, vested choir processing down the aisle, a priest in cassock and chasuble censing the altar and then chanting the Eucharistic prayer–I love that too. Even more.

It’s “holy envy” with a back-beat, a reset, a return. Having gone home I come home.

Thanks to you, David (and Stendahl) I have now a name for what moves me so.

Yes, that’s the surprising dynamic—that the more we are taken with the gifts of the other…the more we end up appreciating our own gifts.

I am the mother of the bride and the mother of the groom. That is true, because Nigerian weddings believe God joins the bride and the groom and Marries their families as ONE.

The groom’s mother is now my sister. The groom is now my son. Everyone hugs us and welcomes us, reassuring us, that our daughter will always be loved and cared for as their own.

I thank God that I have been richly blessed with such a dear son and this loving family! As you described David, the Nigerian ceremony was joyful and sacred.

David, you’ve wisely perceived that, “we have much to receive from those so unlike us.” Oh, how we widen our perspective when we choose to look through another’s eyes. That is how God helps us to see more of what He sees: that God created all of us, and is within each of us. This was a celebration of God’s love being shared. Both traditions of the wedding ceremony reflected God’s presence. We thank you for presiding with such an open heart!

That opening sentence really threw me, Ann—when you said you were the mother of the bride and the mother of the groom. I wasn’t prepared for the wonderful explanation that followed. One more remarkable aspect of the Nigerian tradition that demonstrates its powerful commitment to family and communal unity that is so unlike the culture we live in. We need that.

I now also am reveling in the contemplation found in contrasts, like the weddings noted above.

I am missing the cultural differences I encountered while working in a hospital, but the memories of shared food from regions of Africa will not leave me anytime soon.

I too am glad to have a name for my condition when viewing pictures of wedding celebrations from Eastern countries with innumerable strands of gorgeous orchids hanging from the high ceilings of the reception hall.