Proud Flesh

It was a small procedure, but even “minor” surgery requires general anesthesia, intubation, and signing a form that says if you die in there it’s not like they didn’t warn you.

I walked into the OR in my johnny coat, an IV dripping in my arm, and there before me was a narrow operating table with arms that swing out like the horizontal arms of a cross. I had only seen this strange altar in images of prisoners condemned to death by lethal injection, their arms strapped to the crossbeam of their medical gibbet. It wasn’t a great start to the “procedure.” I lay down, nevertheless, stretched out my arms and fell fast asleep.

For the first few days, there’s nothing to do but sit or lie quietly. Even with meds, there is pain, dull ache. Pain is a funny friend: it focuses our attention on what’s happening right now, doesn’t allow our minds to wander beyond this. In this way, pain is a remarkable form of meditation which I do not recommend if it can be avoided. I inspected my visible incisions, and imagined the invisible wounds in the dark of my belly, which stood in for all the unseen wounds of psyche and spirit.

What am I supposed to do with these wounds? I don’t want them. They seem like glaring evidence of my mortality, of the fragility of my flesh. Maybe it’s because being hurt means sitting alone, in pain, while the world goes merrily on around you, but licking our outer wounds often puts us in mind of our inner lacerations—cuts and bruises from others, and, worst of all, the self-inflicted jabs. They resist every form of healing, for years.

In my pain meditation, I am reminded of a few striking lines from a Jane Hirshfield poem:

And see how the flesh grows back

across a wound, with a great vehemence,

more strong

than the simple, untested surface before.

There’s a name for it on horses,

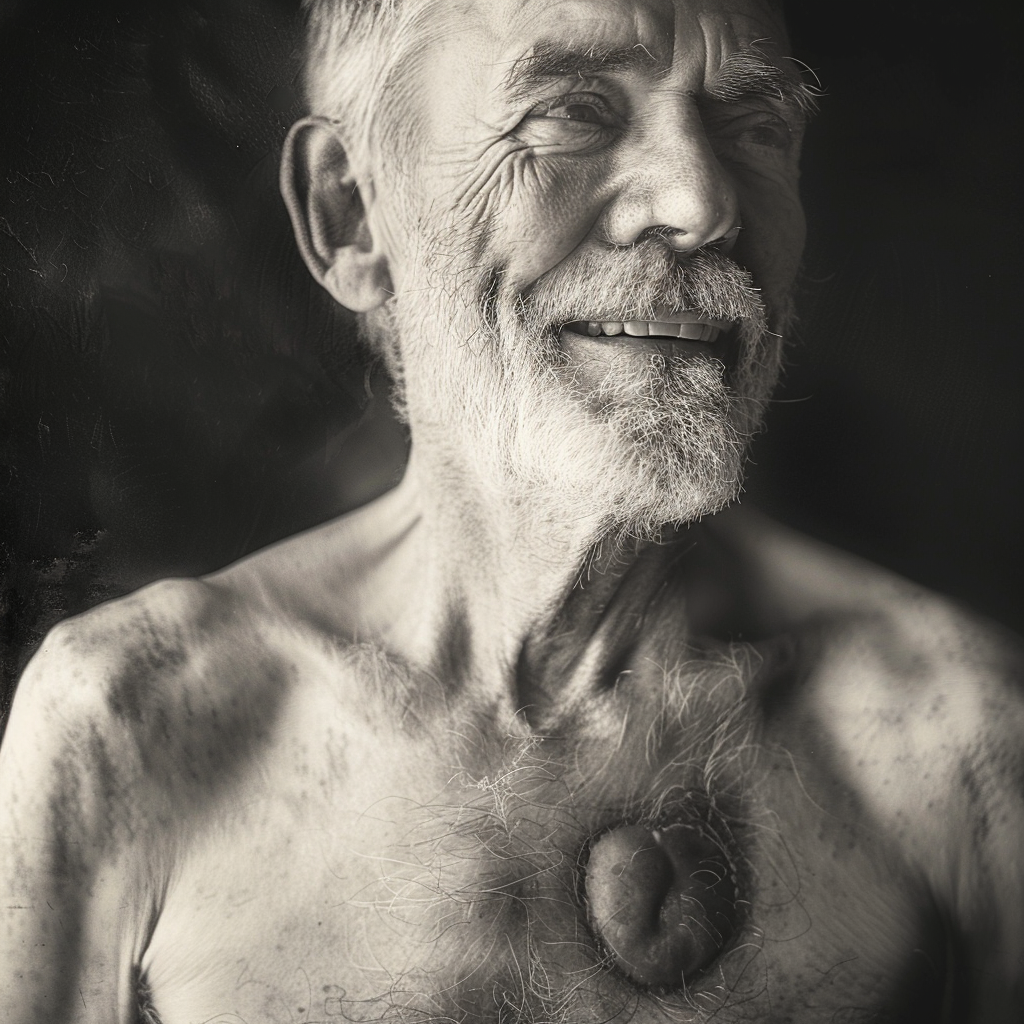

when it comes back darker and raised: proud flesh,

as all flesh

is proud of its wounds, wears them

as honors given out after battle,

small triumphs pinned to the chest—*

I was struck by the “vehemence” of that scarring flesh—this is quiet but forceful work. The body takes its blows and does not go into hiding. It does not believe in plastic surgery, but highlights the gash, makes a show of its healing. It is damn proud. It’s another version of the “sacred wound,” where we are saved not by escaping unscathed, but by looking deeply into those inevitable wounds and knowing they are the only openings where grace and mercy can seep in, knowing they make us stronger, more deeply human.

When confronted with our wounds, what if we could see not shame flesh, fear flesh, or ugly flesh—but proud flesh?

*from “For What Binds Us” by Jane Hirshfield

Pride isn’t the emotion usually associated with scars, but, maybe like crows’ feet/laugh lines, it should be. Outer signs of inner healing. Thanks, David.

No, pride isn’t usually associated with our scars, which is why Jane Hirshfield blew the lid off my mind with that poem.

David, this is brilliant.

Thank you, Michael—what’s brilliant is the Jane Hirshfield poem.

There’s a sign above my desk that says, “Scars are like tattoos but with better stories.”

I don’t know who said that, but it should be in the Bible.

There’s a sign above my desk that says “Scars are like tattoos but with better stories.”

Hey David, thanks for taking us with you into the OR.

Just yesterday, Kasper and I were having lunch with a friend was scheduled for surgery. Kasper quoted Chuck Palahniuk: “It’s so hard to forget pain, but it’s even harder to remember sweetness. We have no scar to show for happiness. We learn so little from peace.”

I’ll send your nephew this link. He’ll love it.

Thanks—never heard of Palahniuk, but that’s a great quote.

Powerful imagery David! Chuck Palahniuk wrote the book that became the movie Fight Club.

Interesting–I went online and looked at some of his other books. Thanks for the tip.